Many years ago, I read an interesting article about a self assigned project in National Geographic magazine.

It was about a guy who, for reasons that escape me now, was destined to move from the city to the wilderness.

I don’t recall if this was a work-based move or if it was just because he wanted a change of scenery, but I do remember that he specifically set himself a daily photographic challenge to make one interesting image each day.

I sort of scoffed at this idea because I thought at the time it wasn’t much, until I went on to read that he was using an old view camera to do this – essentially a mechanical camera designed to shoot only one frame at a time onto 5×4-inch sheet film.

Because these cameras take time to set up, compose, and shoot – plus it was revealed he limited himself to one sheet of film a day – I began to appreciate the difficulty of making that goal come true.

And of course, don’t forget that this was in pre-digital days, so unless he spent a lot of time on shooting Polaroids (single shot positive film used to check exposure, lighting and composition) before exposing his sheet of real film, he’d have to be very thoughtful of the entire photographic process, from lighting to composition, to exposure, and ultimately to achieving his goal.

On reflection this shooting process seems to be the direct opposite of how most photographers work today.

One challenging self-assigned project could be to document something that’s right in front of you: your own home town. In a world where many of us travel extensively, recording your home environment can be a surprising challenge. Photograph by Robin Nichols

With digital, we have a Polaroid-type function built into the camera in the form of an almost instant pictorial result.

Though we can check the lighting, composition, and color almost immediately on the LCD screen, we often don’t, and then we curiously wonder why the result is not to our satisfaction.

We have become lazy, assuming (incorrectly) that the fabulous technology packed into our cameras will somehow automatically correct everything that might go wrong with the shot!

Clearly it doesn’t, and one of the reasons why this happens is that we no longer look at the scene with photographer’s eyes before pressing the shutter release button.

To learn how to truly ‘see’ an image, we have to think about the lighting first.

Reflecting back to that previously mentioned National Geographic article, it cost the photographer $20 every time he pressed the shutter (i.e. unexposed film cost, plus processing).

To learn how to truly ‘see’ an image, we have to think about the lighting first.

With that cost per shot, you might either just give up photography on the spot or take up golf, or you might think a little more before taking the plunge and investing the money into the shot.

You might also spend more time checking your results each time, to see if what you got was close to how you imagined it was going to be.

Expanding on the theme of recording your own place of residence, I often like to seek out completely different photo aspects in one of the most visited cities in the Southern Hemisphere: Sydney, Australia. The challenge is not to do the obvious and snap the Harbour Bridge or Opera House, but to find interest elsewhere – such as in this example deep in the back alleys of the city. Photograph by Robin Nichols

Another negative effect that modern camera technology has had on our creativity is the rapid uptake of the zoom lens.

Don’t get me wrong, zooms are brilliant, and I use them all the time; but they can also make us very lazy, especially when it comes to composition.

Although a good zoom can be used to create different compositional results simply by rotating the zoom ring, it doesn’t stimulate creative thought nearly as effectively as when you have a non zooming lens – a prime lens – which forces you to physically move to get the best angle, lighting, or mood.

I’m sure you all understand where I’m coming from.

What you’ll learn in this article:

- How to assign yourself photo projects – what to look for

- How to choose a subject that might challenge and ultimately help you develop your photographic style

- Ideas on how to get feedback on your work

- Learn about websites that provide professional photo feedback for those with commercial ambitions

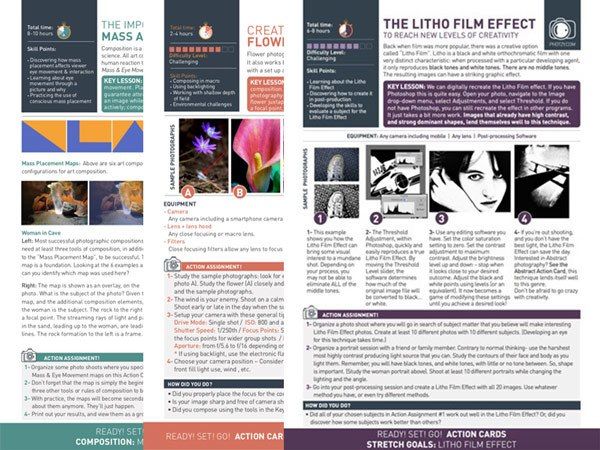

Recommended Reading: If you want to avoid boredom and repetition in your photography, you can inject some creativity into your work by using the fun and challenging assignments in our Creativity Catalog. Go here now to take a look!

Rarely do photographers step completely outside of their shooting comfort zones, but doing so can be quite liberating. In another exercise example, I deliberately added excessive motion to create a series of abstracts taken at a botanical garden resulting in these unpredictable light paintings. (ISO 100, F18 @ 1/4s + fast, sweeping camera movement.) Photograph by Robin Nichols

The Benefits of Self - Assigned Learning Projects

A self-assigned learning project is a terrific way of forcing yourself to move into new and perhaps daunting areas of photography.

A huge advantage of this kind of project is that you can complete assignments on a day-by-day or weekly basis from your own home, thus fitting it into your busy lifestyle.

As an example, I’m at my happiest when out shooting wildlife, especially if it’s in Africa – but that’s an expensive exercise. If I want to try out a new lens, Speedlight, or wildlife shooting technique, I simply concentrate on the wildlife that lives in my neighborhood.

It might not be quite as spectacular as a dawn drive though the Serengeti, but it can nevertheless provide some surprisingly good results while providing you with invaluable experience before you spend money on a big trip.

I recently bought a Speedlight extender (for illuminating distant wildlife) and spent several hours at the local wetlands experimenting with the new gear. Pushing yourself to learn not only expands your technique but also makes it easier to hit the ground running when you eventually land in a totally new

location.

Despite having shot weddings (fast paced and unpredictable) for nearly a decade, one of my subject shortcomings has always been street portraiture, especially when I travel.

To help me get into the zone, I often only take one lens out for the day. Inevitably, this is an 85mm portrait lens which, because it’s not good for landscapes or interiors, forces me to deal with people.

If I carry a wide zoom, I’d probably take the easy path and shoot landscapes instead.

Key Lesson: Limiting your equipment is a good way to focus your creativity.

Recommended Reading: If you want to avoid boredom and repetition in your photography, you can inject some creativity into your work by using the fun and challenging assignments in our Creativity Catalog. Go here now to take a look!

It’s a good idea to set yourself up with a specific project to learn how to use a new lens (for example), especially if you have trouble with focus and sharpness when shooting dynamic subjects like sports, nature, and action. Photograph by Robin Nichols

Ideas for Self-Learning

Everything depends on what it is you’d like to improve: craft, subject matter, or just new gear.

Learning to See #1

Try disciplining yourself to shoot one ‘interesting’ picture a day. If you are busy and don’t have much time, consider completing the exercise using a smartphone rather than a camera, and shoot at work or perhaps when commuting.

If a daily target is a little strenuous, try shooting one thoughtful image each week. And don’t leave it to Photoshop to ‘fix’ the result if it doesn’t work out the way you wanted it to.

Learn from your mistakes and apply what you learn next time you shoot.

Learning to See #2

Try shooting with a prime lens for a month.

An obvious choice might be a 50mm lens because this is a useful focal length for many subjects. Its wide maximum aperture also produces sublime out-offocus backgrounds. Plus, you can pick one up quite inexpensively (from around $130).

If you don’t own a prime lens – or don’t want to buy one – I’d set myself a specific focal length (let’s say 40mm on your zoom lens), then hold it there by taping down the zoom ring so it doesn’t move around (use paper masking tape to do this – it’s not too sticky and it’s easy to remove).

Learning to See #3

Note: If the camera is set to record JPEGs only, you’ll get a black and white JPEG image. If it’s set to shoot RAW files only, it looks black and white on the LCD but reverts to color once downloaded. If you set it to record RAW + JPEG at the same time, it appears black and white on the LCD, but the RAW file will remain in color, giving you a choice once it is downloaded.

Recommended Reading: If you want to avoid boredom and repetition in your photography, you can inject some creativity into your work by using the fun and challenging assignments in our Creativity Catalog. Go here now to take a look!

Learning to See #4

Another perception challenge is to spend a month or so shooting a subject that you’ve never tackled before. This could be anything from portraits to sports, landscapes, news events, or documenting the environment.

We all tend to get our cameras out when we go on a trip, but it’s actually far harder to create something interesting from the environment that you experience every day. So, a great place to start would be a series of images in your own neighborhood.

Learning to See #5

Move out of your comfort zone. Shoot at the opposite end of where you normally would shoot. For many this might be to forget about ‘general scenes’ and go very close, or maybe to shoot some still life arrangements.

By changing your subject matter, depth of field, lighting, and point of focus will become new and provide a learning experience.

The Easter Show in Sydney is a great place to record a wide range of photographable events, from action to portraiture, candids, and still life. In this triptych I recorded the process of weighing and sizing an axe man’s tool of the trade before the final frenzied attack on a wooden pole, on the right. Photographs by Robin Nichols

By changing your subject matter, depth of field, lighting, and point of focus will become new and provide a learning experience.

Learning to See #6

Become a photojournalist for a month. Shoot a series of pictures that tell stories.

This might be events in your neighborhood or something in the city – maybe a festival, surf carnival, or even a country show. Any special events will do.

Set yourself a goal of producing five to ten images and see if you can shoot and edit these to reflect the subject and atmosphere that you experienced at the time.

As a bonus, photographers with such pictorial stories can always find better markets to sell their work, especially if the images are accompanied with appropriate text. Being a bit of a writer certainly helps.

Shooting a photo story for a newspaper or magazine, even if it is just on spec, can be tricky, especially if it’s an open-air event like the Elvis Festival held in Parkes every year. You have no control over the weather, the contestants, the lighting, or the positioning of the performers. You have to learn to be very quick, a bit devious, and to be consistent in what you shoot in order to document the event and produce a group of images that an editor might want to publish. In this example, I had to be very quick to get the shot, as these three Elvises were constantly moving in and out of view. Sometimes you get lucky. Photograph by Robin Nichols

I was quite pleased with this group of portraits. Most were shot with an 85mm lens – it’s not so good for wide scenes or extreme closeups, but choosing a specialized lens like this forces to you concentrate on one type of subject which in turn creates a stronger ‘look’ to a group of images shot at the same time. Visual consistency is an attractive component for creating marketable images. Photograph by Robin Nichols

Feedback is Vital

If setting a photographic project for yourself isn’t already hard enough, getting well-considered and constructive feedback on such efforts might be.

As with any new skill, feedback – in the form of comments, marks, praise, or constructive criticism – can also be seen as an important learning tool. But this comes with certain risks.

If no one ever gives you accurate and honest feedback on your work, you might continue in life thinking that you are the hottest photographic talent on the planet.

Constructive feedback allows you to improve your craft. No one is really 100% perfect in what they do – even some professional photographers will admit that there are usually things they might have done differently given the chance. Hindsight is a great thing.

If no one ever gives you accurate and honest feedback on your work, you might continue in life thinking that you are the hottest photographic talent on the planet.

I think the trick is to positively seek out feedback – whether this be from a friend whose judgment you respect, a mentor at a camera club, or from postings on social media. Use feedback to learn from any mistakes that you might have made, and then try to improve on it for next time.

Sometimes this can be tough.

A rejection from a magazine or newspaper might be a depressing shock the first time it happens, but in reality it might have nothing to do with your image

quality.

It could just be because the images you submitted weren’t relevant to that publication at that time.

Calling ahead to see what an editor is looking for is an excellent way of saving you a lot of time and angst. Conversely, if a submission is successful, it can be a huge boost to your confidence and would encourage you to stretch yourself even further.

Tips for Getting Feedback

Post Your Work on Photo-Centric Social Media

Try sites such as Flickr, SmugMug, Instagram, 500px, and maybe even Behance.

Take any feedback with a pinch of salt, and only listen to constructive commentary.

If you get negative reactions and they are not backed up with a valid reason, ignore it and then move on. “I don’t like this…” is a meaningless phrase, but “I don’t like this because the subject isn’t sharp and the background is a bit distracting…” carries a little more credibility.

You could choose to ignore a remark like this, or have a good look to see if what they say is true, and then perhaps decide what you can do about the sharpness and the background the next time.

Join a Camera Club

These organizations have regular competitions where the results are (usually) judged by visiting experts, professional photographers, or senior members from the club circuit. It’s a good way to not only garner some meaningful feedback, but also to gain technical and creative knowledge from more experienced members in the club.

Try Signing Up for a Course

Most local evening or adult education colleges run photo courses. These are good places to meet likeminded people, learn new techniques and, hopefully, get critical feedback on your work.

Sign Up for an Online Photo Class

This has the advantage of being available at any hour so would suit time-poor students perfectly. I have been involved with online teaching for more than ten years and know that if you are a motivated student, you can get a lot out of the experience.

Unlike face-to-face classes which have distinct time restrictions, an online environment is ideal because you can ask a lot of questions over the week or month the course might run for, and therefore garner a great deal of valuable information.

Upload Your Images to a Specialized Photo Critique Website

There are quite a few organizations that offer creative feedback to aspiring photographers. This is a better option than uploading your work to Flickr, for example, because the commentators are all professionals. Take a look at sites like Kelby TV’s The Grid, Professional Photo Critique, and 1X to start with.

If you are not good at shooting people and events, maybe try shooting candids at any of your local town’s many shows. I love the Easter Show in Sydney, because there’s usually so much happening – plus there are so many great opportunities for candid photography. This teaches you to be alert, to predict what might happen by observing people, and above all, to be ready to shoot in an instant. Above left, seen at a flyball competition; above right, a dog owner gets the attention of her competitor with a treat. Photograph by Robin Nichols