I PHOTOGRAPH, therefore I am.

We are all shaped by life events. For me, photography was, and still is, a life event, my bright spot. I’m not a young guy. Since I was widowed a couple of years ago, I think it is fair to say that photography has saved my life. Photography isn’t just what I do; it is who I am. Photography defines me.

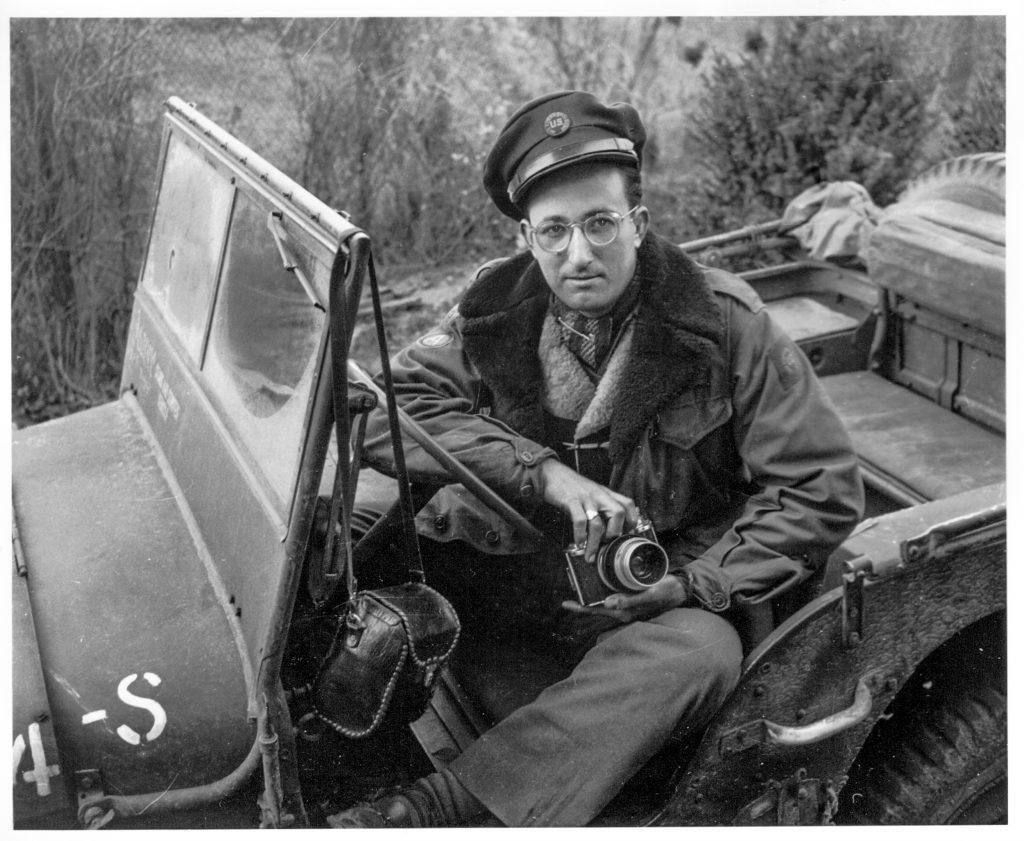

I was almost literally born into photography. My dad was a full-time professional photographer working for Acme Newspictures. Acme hired him straight out of high school, in 1934.

By 1944 Dad was a 28-year-old war correspondent for Acme in the European Theater. He was one of the first correspondents into Paris in August, 1944, in a jeep filled with guys racing to catch General Leclerc at the head of the Free French column. At one point, delirious Parisians who recognized the American uniforms overwhelmed his jeep.

But a sniper across the boulevard opened up, the guy driving the jeep floored it, and Dad, who was perched on the spare tire taking pictures with his big 4×5” Speed Graphic press camera, was dumped unceremoniously into the street.

No one was hit. Dad was bruised and humiliated, but otherwise unharmed. Anyone who remembers the nearly indestructible Folmer and Schwing Speed Graphic camera can relate to the old joke that one can fold it up and batter their way out of a riot zone with it.

After the war, Dad and a few other guys left Acme to form their own outfit in New York City. They called it Camera Associates. Mom would often take me to visit as a toddler. I would stand on a stool in the print darkroom so I could peek over into the developing tray and see the ghostly image beginning to appear on the paper as the tray was gently rocked. The aroma of what we then called “hypo” (acetic acid stop bath and fixer) was in my nostrils from age three. To this day, I love that nostalgic fragrance that many call a stench.

Photography isn't just what I do; it is who I am. Photography defines me.

I know very few photographers my age and even much younger who don’t have a variation on that theme in their experience, the almost magic of seeing that faint image just beginning to form under the dim amber safelights of a darkroom.

But bad luck struck in 1952. My dad died of a disease no one had ever heard of, and my devastated mom discouraged me from entering into photography. I don’t know why, but she did, and I was a little kid who did what Mom said. I did not pursue it even though on some level I wanted to.

In 1961, I went into the U.S. Army. I was posted to Germany but went without a camera because I had read an article that asserted “no one wants to suffer through your lousy travel pictures, so just take them in your head.”

That article might have been satirical, but I was 19 and dumb, so I took no camera to Europe. In hindsight that was very shortsighted and imparted a basic photographic lesson: TAKE! THE! PICTURE! Indeed maybe no one else wants to see it, but you do!

When I came out of the army in 1964 and got a job, photography still seemed to be calling to me.

I had some money in my pocket and Polaroid had just introduced the Swinger, a little $20 black and white peel-apart instant camera. It was heavily advertised for its fun factor.

Polaroid Land “Swinger” ca. 1965. By Camerafiend at English Wikipedia, CC BY 2.5. Photo from Wikimedia Commons

The Swinger was lots of fun! And very limiting! But I liked the instant gratification aspect a lot, so I bought a more sophisticated model.

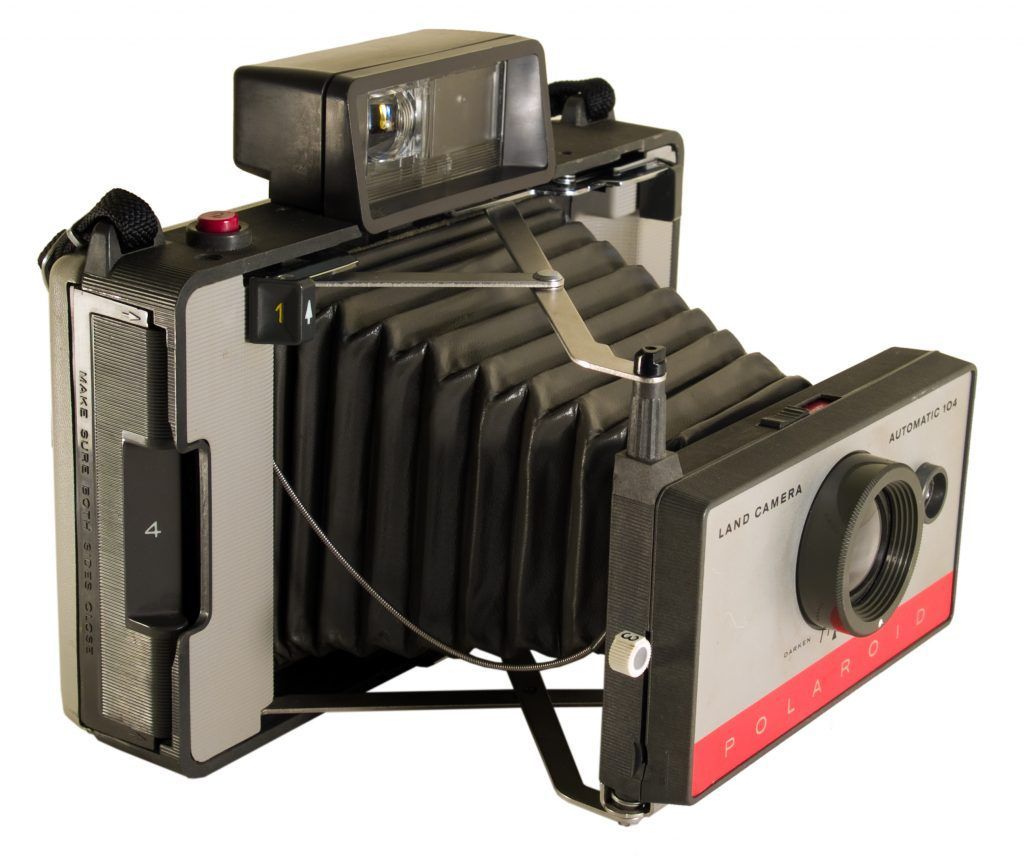

With my new Polaroid 104 I began taking pictures for bulletins and newsletters of activities in a church youth group. At some inevitable point I was asked to take pictures that the Polaroid simply could not handle. I explained the technical limitations and a parishioner offered to lend me his VERY expensive 1964 Pentax Spotmatic 35mm SLR, the first SLR with through-the-lens metering.

I totally blew that job.

I had no clue what I was doing. I didn’t know an f/stop from a fan belt. None of my attempted pictures “came out,” as we said back in the day.

I was humiliated, and mad. I went out and bought my own SLR. I was determined I was going to learn photography and never embarrass myself like that again.

Polaroid Land Camera Model 104 (1965). Photo by Tim Williams

I went hammer and tongs. I bought a developing kit with a tiny enlarger. I blacked out my apartment kitchen with black plastic trash bags. I immediately needed a bigger, better enlarger. I thought I was doing great until somebody who knew stuff pointed out that my prints were flat and muddy—turned out my “safelight” wasn’t safe and was fogging my paper.

There’s an old joke among professional photographers:

- You start out taking pictures for fun…

- Then you take pictures for friends…

- Next thing you know you are taking pictures for money.

We’ll briefly discuss the following:

- Why take pictures?

- “Snapshots” are photography.

- Photography is the keeper of the historic flame.

- Photography teaches you to see, to be observant.

- Photography gives a creative outlet to those who can neither draw nor paint.

- Make mistakes! They are great teaching tools.

Recommended Reading – Want to learn how to make your photos stand out from everyone else’s? Grab a copy of Photzy’s premium guide: Effective Storytelling.

Why Take Pictures?

Why not? I approach this article from the perspective of one who took a degree in commercial photography, worked at it full time with my own studio for 16 arduous years, lost the studio owing to poor business skills, hung up my guns and essentially refused to even pick up a camera for 13 years, only to be suddenly head-first re-immersed in photography with a tiny pack-of-cards shirt-pocket point and shoot.

For me, digital is where photography really begins, the second verse. The irony is that thanks to digital, photography means more to me now than it ever did in analog.

I was determined I was going to learn photography and never embarrass myself like that again.

All my years of education and experience taught me everything I would ever know about photography – I thought. I was proud of what I knew and could do with a camera. I was especially adept, as Saint Ansel (Adams) once remarked, at “knowing where to stand,” that leading-of-the-target sixth-sense of being in the right place at l’instant décisif, eye to the finder, primed to shoot, and thrilled to my core when I nailed it, giving myself a mental fist bump.

The 2007 Nikon L12 point-and-shoot camera retailed for about $100 USD. Photo by Chuck Haacker

Once I left the profession, though, I thought I would never again know that thrill… until I dipped my toe into digital. Then I went in up to my knees. Twelve years in, working with excellent mirrorless cameras, volunteering as an event photographer for as many non-profits as will have me, I am fully re-immersed and thrilled to find that I’ve still got it! 76 going on 77, and I’ve still got it! For me that’s beyond huge; it is life giving, and lifesaving.

Memories are made of this. For me, the thousands of digital pictures I made while my late wife and I were on our road trips are priceless. I can relive a whole trip perusing my Flickr albums, meticulously post-processed and assembled in specific storytelling order. For all intents and purposes, they are free! Sure, my cameras cost money, but I rarely print anything, preferring an online presence. I can share everything or specific things via links and need never spend a penny.

Snapshots Are Photography

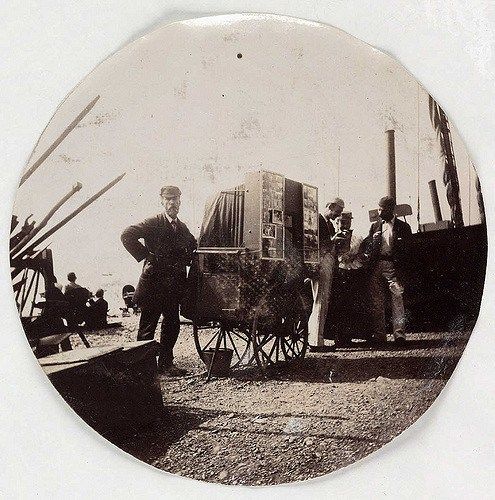

This is a “snapshot” picture from about 1888-1890 made with an Eastman Kodak no. 1. This is the hand-held you-pushthe- button-we-do-the-rest camera that changed photography forever. We know it was a no. 1 because the print is round. It’s an excellent photograph, well composed, interesting, and showing an attractive and athletic young woman in what we now call “period costume” rowing a boat. It raises all sorts of questions: Where is she? What has captured her interest off to her right? How in the world can she row in that wasp-waisted corset? Where did she get that awesome hat?

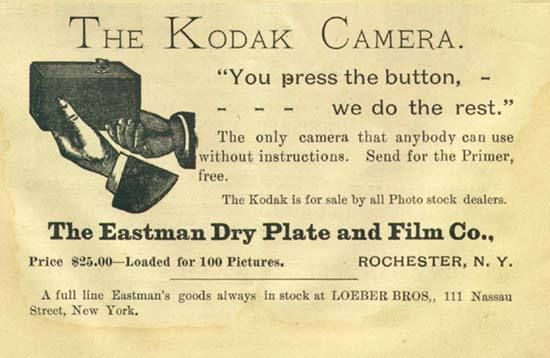

“Saint” George Eastman firmly placed photography into the hands of nearly everyone who could afford $25 USD, which is nearly $700 in today’s money; nevertheless tens of thousands paid it and continued to pay it, just for the sheer fun of photography.

I think it is very important not to denigrate so-called “snapshots.” 90% of all pictures ever taken are probably not very good, but what matters is not so much the quality of the picture but rather the tiny slice of space-time it captured.

The Keeper of the Flame

Photography is history on the hoof; it has been since its inception in France in the years 1829-1839. I love history. I feel that photographs connect us with the past with greater detail and immediacy than paintings are capable of. Photographs have a kind of time-machine quality.

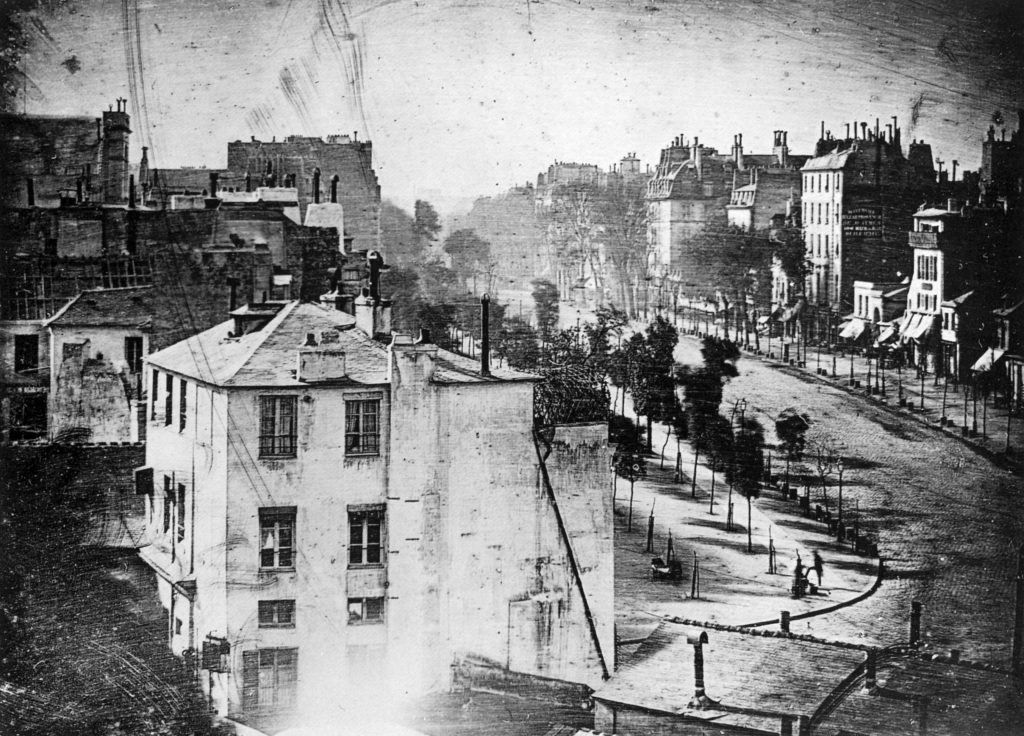

This ordinary street scene Daguerre made seems devoid of people except for a man getting his boots blacked down in the lower-left corner. That’s because Daguerre’s exposure, with his slow materials, probably took around 10 minutes. A boulevard crammed with people appears eerily empty. This, by the way, is a trick you can still use, piling on neutral-density filters to make your exposure long enough that people moving through the scene no longer register. They are only visible if they hold still.

Daguerre’s picture shows precise detail that most painters would probably leave out. Endless chimney pots. You can count the cobblestones in the street and the exposed bricks in the nearest building. Even the most meticulous of genre painters might be inclined to edit out such exquisite detail, but the photograph, even taking 10 minutes, takes it all in.

Daguerre did what a lot of us do with a new camera: pointed the thing out the window and shot. But this genre, the cityscape or landscape, is as old as art. Would Daguerre have realized at the time that he was photographing history? Does the scene look like that now? I bet not. Many of the buildings will have been displaced by newer ones. The street itself may have shifted. The building Daguerre was in is probably no longer there. In short, the scene he captured is now irretrievably gone, but the photograph endures. It allows us to see what was, as if it still were, keeping the flame alive.

This group is identified only as “Late 19th Century Family” on the free site where I found it. Photo from Public Domain

We cannot know who these people were, or even where they were. They stare back at us through the literal lens of history. This genre of picture was very common in the period. Itinerant photographers, most working in the wet collodion process, so they had a darkroom on a wagon, would come to the door and offer to take the family group photo with their house in the background, preserving the two most important things: home and family.

I feel that photographs connect us with the past with greater detail and immediacy than paintings are capable of. Photographs have a kind of time-machine quality.

These were living, breathing, and quite ordinary human beings exactly like us, being memorialized at a time when it had become possible for quite ordinary human beings to be so memorialized. Painters were and really still are for the one percent. We only have pictures like these because of photography. In a sense it is miraculous.

Photography Teaches You to See!

Margined leatherwing beetle on an Echinacea. Photo by Charles Haacker

Looking is not the same as seeing. We all do it, but photographers learn to pay attention, to truly SEE. Do it enough and it becomes automatic, second nature. I was out looking for flower close-ups one day when I saw this tiny margined leatherwing beetle hunting aphids (image above). I liked the curve of her body in the sunlight on the Echinacea. She made a possibly mundane flower close-up a little more interesting for having seen her.

Recommended Reading – Want to learn how to make your photos stand out from everyone else’s? Grab a copy of Photzy’s premium guide: Effective Storytelling.

In a children’s museum, my son and granddaughter discovered a shadow or silhouette wall. I wasn’t at all sure I could even capture the result with a hand-held camera, but I certainly was going to try. Photo by Charles Haacker

Seeing the Light

Learning to really see the light itself is huge. It is a learned, acquired skill, and (bonus) you can even practice it without having a camera. My wife and I made a lot of road trips, and, often, coming into camp in the golden hour, I would be suddenly excited by the awesome beauty of the light itself. I would just SEE it! What was most arresting was the translucency of subjects glowing in the lowering sun. I gradually realized that what I was seeing was the character of back light: light coming from behind the subject toward the lens. It became my favorite light for just about everything.

This picture was made while out looking for fall color, but I knew I didn’t want to just take pretty pictures of shiny red and gold trees; I wanted to emphasize that glow, so I deliberately chose to get in close, get the gold, and let the red fall out of focus in the background.

More recently I was out walking and saw these dead, dry oak leaves.

By getting in very close with a 10mm extension tube and watching for the sunburst through the edges, I made something dead and dry into something I think is abstractly pretty.

Photography offers creativity for those who can neither draw nor paint.

On the anniversary of my wife’s death I went for a drive, something she loved, to look for a sunset in her honor. I found this:

That original raw capture is pretty bleh. I knew what I wanted. I knew how it was supposed to look. But photography often cannot capture the scene as felt owing to limitations of the medium; there were things working against me. If I were a painter, I could paint the scene as I saw it in my mind’s eye (there really is a mind’s eye and artists are urged to develop it). I can neither draw nor paint, but I CAN literally develop a photograph to show what I meant it to show, and share the emotions I felt in the moment, like this:

I call it Daphne’s Sunset. It started with a raw capture (I’m an unapologetic total raw freak), but it could have been done from a JPEG. In fact, a straight-out-of-camera JPEG probably would have looked closer to this without processing. I won’t go into the steps I used in Lightroom and Photoshop to arrive at this version; just compare the original with the processed version.

Post-processing is sometimes denigrated, accused of being somehow “lazy” or “dishonest.” The term “Photoshopping” or “‘shopping” is used as a pejorative, possibly because there are many, many dishonest pictures being displayed without full disclosure, but I call bullpucky on Daphne’s Sunset being dishonest. The eye is capable of perceiving so much more detail on the scene, but what many people are missing is that the modern backlit CMOS sensor can record the detail but cannot just spit it out without some processing. Back in the analog days we called it “developing.” The honest version is the processed version; that is what it looked like.

Recommended Reading – Want to learn how to make your photos stand out from everyone else’s? Grab a copy of Photzy’s Effective Storytelling.

Make Mistakes!

“We learn wisdom from failure much more than from success. We often discover what will do, by finding out what will not do; and probably he who never made a mistake never made a discovery.” – Samuel Smiles

I was in a museum, one of my favorite places to photograph, but I wanted to be very discreet in a quiet art museum. My mirrorless Sony A6300 has a silent shutter mode that I thought would be perfect so as not to disturb other patrons.

Wonderful terrible example of rolling shutter banding in artificial lighting. Photo by Charles Haacker

BIG mistake! Do you see it (imag above)? The light and dark horizontal banding looks like ripples on the surface. The effect is caused by the electronic “silent shutter” being out of phase with the frequency (60Hz in the U.S.) of the artificial lights.

It pretty much ruined everything I shot, but it also taught me a valuable lesson: generally, never to use a silent shutter in artificial light. I was shooting only for my own pleasure, so aside from mortification, there’s no real harm done and I won’t do it again.

Screw up. Correct. Learn. Screw up. Correct. Learn. Rinse. Repeat.

If you are serious about photography, do photography. Do lots of photography. Take your camera everywhere, even if it’s just your phone, although I personally prefer a “real” camera owing to it being less limiting and more flexible. But the important thing is to be prepared by having the camera, and to be alert and aware and awake and seeing. The more you see, the more you shoot; the more you shoot, the better you see. The mere fact that you are documenting life has an influence on your life. It will live after you. You are a keeper of the flame.

Self-Reflection Questions:

- Is photography important to you? Why or why not?

- Do you take more or fewer pictures digitally than you did with film?

- Do you think so-called “snapshots” are unimportant throwaways?

- Can “snapshots” be important historical documents?

- Was the invention of photography a historical milestone?

- Do you think that doing photography makes you see and makes you more observant?

- Do you enjoy studying how light affects objects and persons?

- Do you think you should never make a mistake while photographing?