I started taking shooting stock images seriously in the mid-eighties. Until then, my entire contribution to a picture agency I’d joined in London had been no more than a few of my better holiday snaps. But then one day I received $400 for the sale of a photograph of a palm tree taken on a beach in the Maldives. It appeared on the back of a muesli packet, of all places, and, from that moment on, I was hooked with stock photography.

Image licensing, or stock photography, is the process of selling the usage rights of an image to an interested party for the purpose of advertising, marketing, promotion, or illustration. Although a few photographers run their own stock libraries, this process is usually accomplished through a middleman: a stock or picture agency.

Typical clients using such an agency might be advertising companies, marketing businesses, book publishers, small businesses, government departments, picture editors, news media, educational institutions, and even students. It could be anyone, in fact, who needs to have the use of an image but does not have the time, skills, or experience to produce it themselves.

Although a few photographers run their own stock libraries, image licensing is usually accomplished through a middleman: a stock or picture agency.

But is licensing your images a good proposition? Does it make money? Can you give up your day job? And how do you get started?

What you will learn in this article:

- Is image licensing worth your time and effort?

- Why a non-specific image can be beneficial

- What makes a good stock photograph?

- Tips to get you started

- Some stock agencies that you should know about

- How to set your expectations

Back to the Maldives for a moment.

That image, which I had deliberately sought out while on a stopover between London and Singapore, sold for a very specific reason. It wasn’t particularly dramatic, but the sky was blue, the small beach was deserted, and the palm tree in question was leaning out at just the right angle over the crystal clear waters of the Laccadive Sea. In fact, the UK company that bought the rights used the image to promote a competition, the first prize of which was a week’s holiday in a resort which, ironically, was not in the Maldives. Lesson number one is if the image is non-specific, it has a far greater licensing potential than one that can be clearly identified. Consequently, it has sold several times: as a brochure cover for personal insurance, as a front cover for a Qantas promotional flyer and, as in this case, as a generic destination image for a consumer competition. If I had included the resort in the background of this image, it would have had a much shorter sales life, or maybe not sold at all.

Recommended Reading: Want a simple way to learn and master photography on the go? Grab our set of 44 printable Snap Cards for reference when you’re out shooting. They cover camera settings, camera techniques, and so so much more. Check it out here.

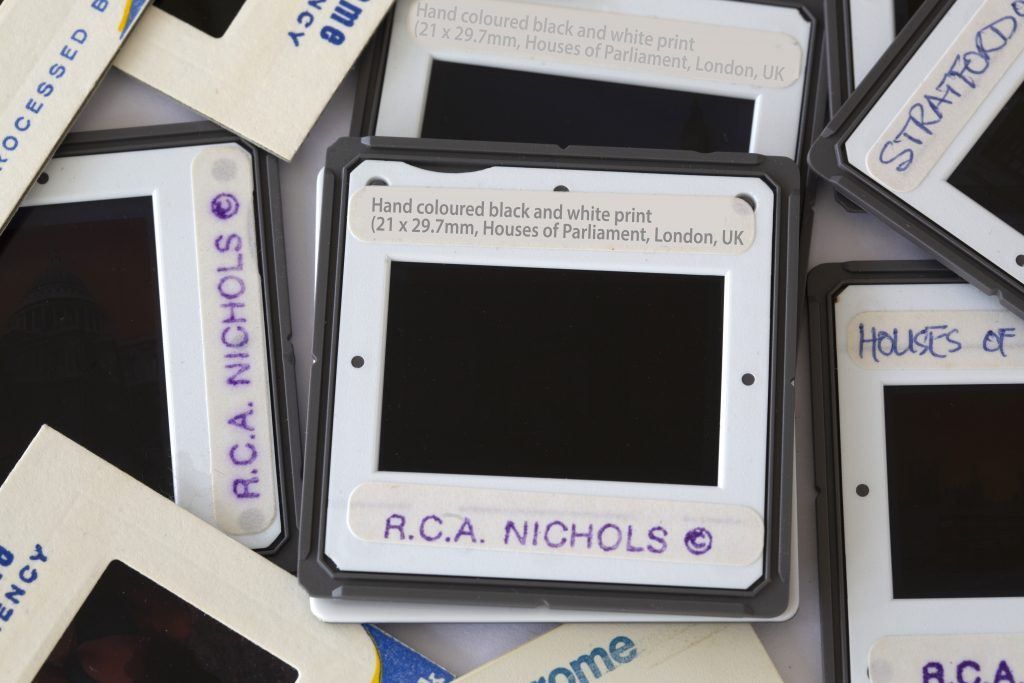

Back in the day, it was tedious to mount every submission in slide mounts, write descriptive labels, and add your contact details on every slide. Current stock submissions also require descriptions plus up to 50 keywords before they are accepted. Photograph by Robin Nichols

What Makes a Good Stock Image?

- The image needs to be technically good

- The image content should be generic where possible

- The composition should be simple and uncluttered

- Leaving space for the later addition of text can be seen as a bonus

- Good images need not be of people or places – stock also includes abstracts like textures, patterns, liquids, minerals, and so on

At the time I was happy to have the cash and to imagine I was on the road to riches with my burgeoning stock photography career. Back then, there were very few full-time stock shooters. Most were professionals working in other fields, who maybe took a couple of extra rolls of film when on location at the end of a job, or perhaps snapped their friends and families when the opportunity arose.

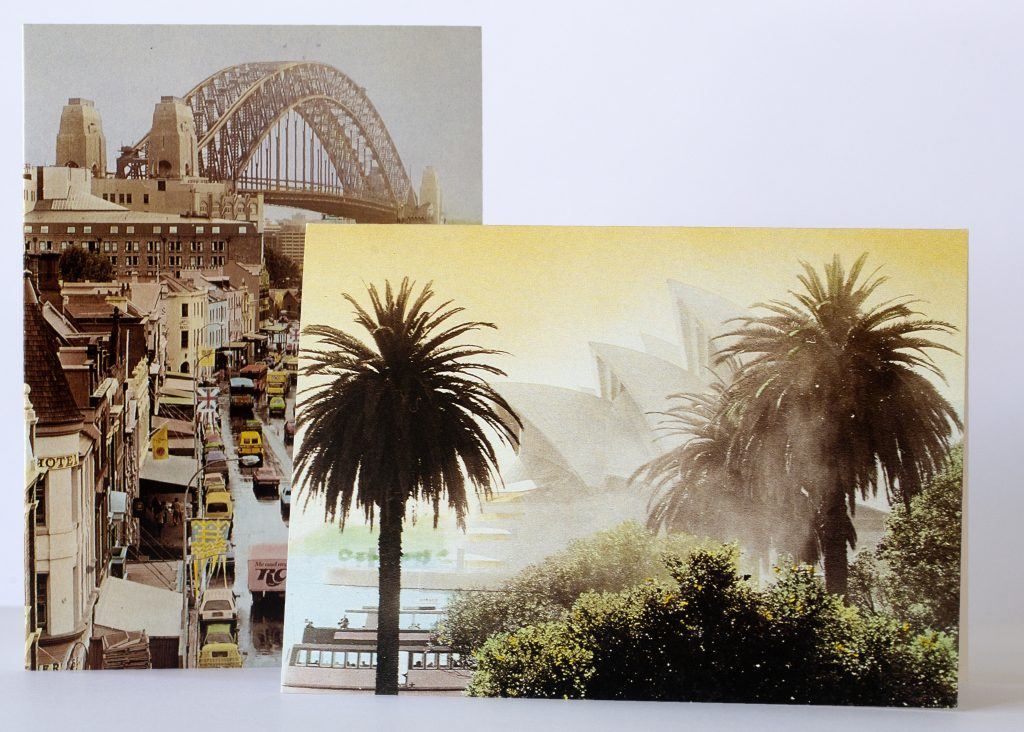

This is one of my earlier attempts to create a photographic niche: a series of hand-colored black and white prints of famous scenes from Sydney. They were picked up by a local card company and published as a series of greeting cards. Photographs by Robin Nichols

When I started shooting stock, many of the smaller agencies were hungry for new material. If a big advertising agency came looking for a series of great shots on a specific subject and that agency didn’t have anything to offer, chances are they’d not come back again. Agencies therefore accepted submissions that would never be accepted now, simply because what had started out as a very basic picture repository for local advertisers had begun to morph into an ever-expanding global marketplace.

That period lasted, for me at least, about 10 years. In fact, I traveled throughout Southeast Asia for more than a year shooting mostly travel-oriented stock, submitting to up to eight agencies at a time. I based myself in Singapore where I’d get my work processed (it was half the cost of processing back home) and then I’d buy another 100 rolls of Kodak Ektachrome and set off to another potential location in the region. It was hard work and, while it never made me rich, it funded travel for my wife and I for 18 months to places I’d never have got to if I’d not been chasing the stock dollar.

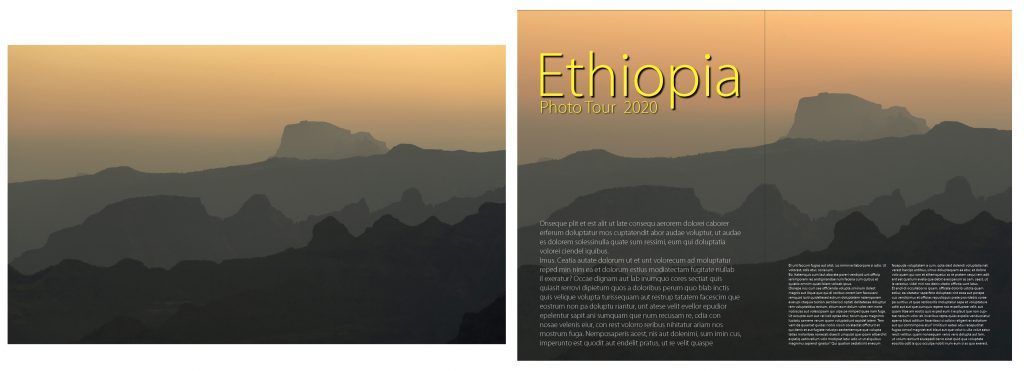

The image on the left is gorgeous but it lacks a clear focus point in the foreground. Sometimes, a relatively empty scene, such as this, is ideal for editorial layout (on the right). Photograph by Robin Nichols

As agencies took on more and more contributors, their picture editors began to reject an increasingly higher percentage of my material. Because so many photographers had jumped onto the stock bandwagon at this time, libraries were rapidly filling with material, so naturally they became increasingly picky about both the technical aspects of the work and its sales potential.

As a consequence, I spent a lot of time and effort looking at what actually sold, against what was being returned to me because it was deemed no longer saleable. I concluded that the two biggest characteristics of a great mainstream stock image – that’s one which is likely to sell multiple times – is that, firstly, it has to be generic, and secondly, its content must be such that it can be used for a wide range of applications.

I concluded that the two biggest characteristics of a great mainstream stock image is that, firstly, it has to be generic, and secondly, its content must be such that it can be used for a wide range of applications.

So, if you get the chance to search for successful stock shots, you might be surprised to find that most are quite unassuming – boring even. And it’s this generic ‘blandness’ that can mean an image is sold over and over, covering all your shooting costs, and making a fine profit. One stock shooter I interviewed a few years ago contributed no more than 100 images each year to his agency and yet made a living from stock alone. At the time, his best shot was an evening shot of a house located on the side of a hill with the setting sun silhouetting a mountain range off in the background. At the time of my interview, the agency had already sold it 27 times, to a bank, an insurance company, a construction company, an electricity provider – you name it, they’d sold the rights to use it. Not bad for a single image.

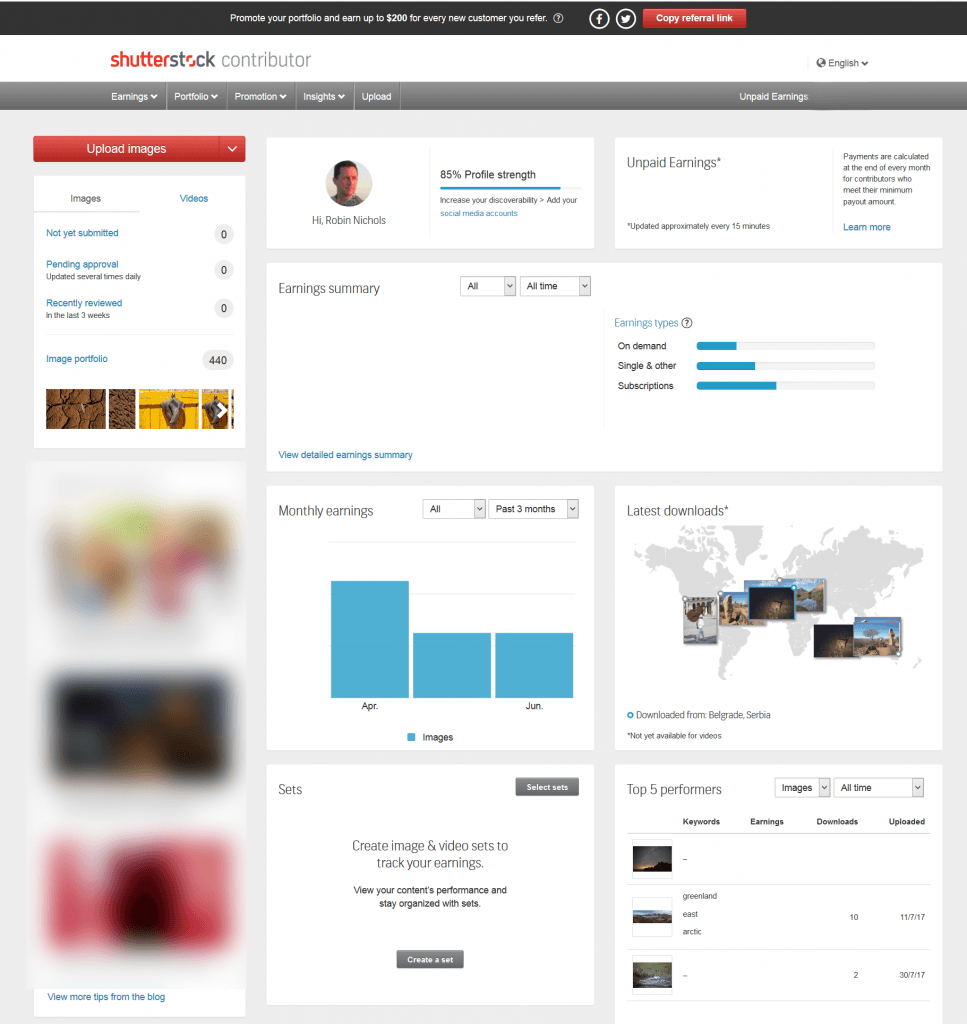

Once you are accepted as a contributor, you have your own login pages which display images submitted, pending, accepted, and rejected, plus sales information, top-performing images, and links to blogs and contributor profiles. Image by Robin Nichols

11 Stock Tips to Get You Started

- Anyone with a creative mind, a lot of patience, and a good technical background can be a stock shooter.

- Everything has more or less already been ‘done,’ so it’s a good idea to research existing libraries, both free and commercial, to get an idea of why some images are free, while others are not.

- Successful stock photographers shoot and submit on a regular basis. This might only be a few hundred carefully selected images per year, but it’s regular.

- Financially, stock can be a gamble. You have to pay up front for all materials, travel, props, and model fees. If it sells, you get a return on your investment; if it doesn’t, then you might be out of pocket.

- Most stock agencies don’t accept heavily retouched images, unless clearly labelled as such. Many agencies promote ‘photography,’ as well as ‘illustration.’ Editing to make the image appear more or less as it was at the time of capture is perfectly acceptable.

- Locations that can easily be identified tend to have a shorter life than more generic scenes. If it’s a city skyline, for example, it might be accurate for a year or two, but skylines change as new buildings appear and old ones are demolished.

- Image locations that are very specific, like the Arc de Triomphe in Paris or the Sydney Opera House, can be used repeatedly, but include people, cars, and advertising hoardings and they might lose their attraction because fashions often dictate their use.

- Niche stock images, especially in the scientific and natural worlds, have the potential for good sales, but then their sales and distribution might also be limited to very niche areas.

- Because stock is primarily digitally delivered, some stock agencies accept smartphone images. Agencies also accept video clips and even current affairs/news clips as stock assets, although from their nature, their relevance in the 24-hour news cycle might be short.

- Images containing recognizable people and property generally need to be accompanied with a model release for each person and the property. If there are no releases, then the image can be sold for editorial use only, which typically generates a smaller return.

- Some agencies commission work, but those jobs are naturally reserved for top-performing contributors.

Recommended Reading: Want a simple way to learn and master photography on the go? Grab our set of 44 printable Snap Cards for reference when you’re out shooting. They cover camera settings, camera techniques, and so so much more. Check it out here.

Adobe Stock is an offshoot product designed to service designers, photographers, and illustrators using Adobe software (and others requiring stock images). Image by Robin Nichols

Digital Stock

Of course, when I embarked on stock photography, I was shooting mostly color transparency material. Digital provides a new way of working with stock. ‘Film’ is free, and, because it costs nothing, you are open to experiment until you get it right. Plus, it’s easy enough for an individual to set up their own stock licensing business – all you need are some great shots, a good marketing technique, a website, and a solid presence on social media to get going.

The advantages of licensing your work through the portals of a commercial stock agency are obvious. These agencies have a reputation for being able to provide almost any type of image and would thus appeal to a wider range of clients than any individual could hope to attract. You sign up, upload your work, and label it, and the quality control, management, promotion and sales are all handled online, at no upfront cost to you; although, clearly this is extracted as a percentage of the sale price.

Stock agencies not only license images, but they also host music, news media, video clips, and (as you can see in this image) 3D rendered objects and textures. Image by Robin Nichols

However, if the work fits a specialist niche – let’s say the insect life of central Borneo – then you are more than likely to understand your potential clientele, however limited that might be. It would be easy enough to approach potential clients personally, and therefore be able to license the work at a far greater profit to yourself.

Top Stock Licensing Agencies

- Alamy

- Adobe Stock

- Shutterstock

- iStock

- Dreamstime

An old man riding his donkey into the town of Trinidad, Cuba. The sign on the donkey’s head says, ‘For rent, photos 50 cents.’ Photograph by Robin Nichols

Nitty Gritty

Before signing up with any stock agency, take a good look at its terms and conditions. You need to understand how much your images might sell for and, most importantly, how much of that published price ends up in your bank account when something sells.

Most agencies license their work in one of two ways: as royalty-free downloads, with set rates for different resolution downloads, and as plans, where the client might pay a monthly fee for a specific number of downloads. Royalty-free suits individuals who might require only a couple of images, while the latter pricing model suits big users such as travel companies, advertising agencies, big media, graphic designers, and so on.

When I started licensing my work, I did so through eight stock agencies at the same time, so I had to shoot eight of everything. This was not only expensive in terms of the amount of film shot, but tedious, because everything had to be individually labelled and categorized before posting off to the agencies. Then, many of these smaller agencies disappeared as they were bought up by far larger companies, like Getty Images, thus making the submission and sale of work significantly more competitive. When I started shooting in the eighties, the deal was that the photographer earned 50% to 60% of the sale price, which was a pretty good arrangement.

Before signing up with any stock agency, take a look at its terms and conditions.

But as the larger international agencies began buying up a lot of the smaller overseas agencies, licenses were watered down again and again to the point where photographers were earning only a percentage of a percentage as work was marketed through a string of affiliates. All but the very best contributing photographers suffered the same.

In the mid-nineties I stopped shooting for stock because sales had dwindled to the point of insignificance.

However, I started submitting to an online stock agency again a couple of years ago simply because in the meantime I’d amassed a huge library of my own work that was little more than existing on a bunch of hard drives in my office. So, I thought, why not?

Recommended Reading: Want a simple way to learn and master photography on the go? Grab our set of 44 printable Snap Cards for reference when you’re out shooting. They cover camera settings, camera techniques, and so so much more. Check it out here.

Free Image Sites

Morguefile has a wide range of free stock, which is mostly older stock images that are deemed no longer commercial so have been released as free downloads. Note that if you don’t find what you are looking for, you can link directly to a number of commercial stock agencies. Photograph by Robin Nichols

- Morguefile

- Pexels

- Pixabay

- Unsplash

- Picjumbo

Clearly, the playing field has changed dramatically in the 25 years since I last contributed. Because all business is now conducted online, and is global, contributing photographers not only have a far wider potential audience, but they also have much greater competition. That said, they also have access to a range of in-depth tutorials on subjects that sell (and why), along with access to a range of sales tools, including blogs, photographer profiles, and many more resources that were never available to stock photographers back in the eighties.

While I think that the heady days of making good money from shooting stock are long gone, I still view it as an excellent way to make some profit from assets already shot. If you have the images, the time, and the creative drive, then shooting stock photography can provide a useful alternative income stream.

Self-Check Quiz:

- What is image licensing?

- Who are typical customers for purchasing stock photography?

- Is it better for a stock photographer to be very specific, or more generic in nature?

- Name three characteristics of a good stock photograph.

- Does a stock photograph always need a person in it?

- Does any stock agency accept smartphone images?

- Can you sell and image with an identifiable person?

- Name three top stock agencies.